Understanding social identity is the secret to great workplace cultures

ALSO: what we can learn from changing student culture

Tapping into the power of us

At the end of the nineteenth century Illinois born psychologist Norman Triplett performed a series of social experiments that seemed to confirm the effect that we have on each others’ work.

Triplett arranged for 40 children to play a game that involved turning a fishing reel as quickly as possible. He observed that those who did the game in pairs were quicker than those who turned alone. Working alongside others made us work harder.

Triplett then studied cyclists comparing the race times of those who raced against other riders, those who had pace setters and those where the cyclist rode alone. He found that those who competed against each other were 23% faster than those who cycled alone.

He kept experimenting with different ways of pitting participants against each other, concluding that the presence of a competitor ‘served to liberate latent energy not ordinarily available’. Competition is good.

A few years late French engineer Maximillen Ringelmann observed what became known as the ‘Ringelmann Effect’. He observed that asking group members to pull on a rope produced less total effort than the sum of their individual attempts. This is idea is known as ‘social loafing’, the idea that we don’t fully apply ourselves when the outcome of our endeavours is hidden in the collective. The idea of social loafing is that our motivation dips when part of a group.

These two ideas have served to form the basis of general attitudes towards work. People work harder when in competition with each other, but they slack off if their work is buried in the output of a group.

But in fact despite enduring in contemporary business wisdom, both philosophies have been challenged by subsequent exploration.

A definitive meta-analysis in 1993 found that ‘social loafing was eliminated when participants worked with close friends or teammates’.

In the original Ringelmann experiment participants had found themselves pulling a rope with strangers. In fact when people performed activities alongside friends they worked harder, demonstrating not social loafing but what was styled ‘social labouring'. We work harder when care about the group we’re working with.

Ok, but what about when this isn’t a group of friends, what would it take to shift a group from a disconnected assembly of strangers to feeling like they were a group? One experiment in Norway recruited a group of teenagers. One group of participants were put into teams. As part of their team ethos they were asked to develop a team slogan, group song or philosophy over the course of a brief 30 minute team building exercise.

Just 30 minutes identity building started some simple magic. The experimenters observed that the groups who had competed without a team exercise had shown signs of underperforming expectations, confirming that 'social loafing had occurred’. But the cyclists who had created the loosest form of group identity demonstrated social labouring, outperforming forecasts.

The researchers concluded that when individual effort couldn’t be perceived then ‘social loafing is likely to occur’ but when a small exercise of building group identity had been achieved it led to teams outperforming their individual talents.

In other words, yes we might slack off if we feel our effort is lost in the group, but when we feel that our group matters we unlock extra effort beyond the norm. There this is transformational ‘power of us’. The study of this ‘social identity theory’ is one of the fastest growing areas of social science.

Today there’s the first of three podcasts about what social identity offers to us, in life and in work. It’s the first half of a discussion with Professor Alex Haslam, one of the most important figures in the study and understanding of social identity.

The second episode next week takes us into the implications of social identity for leadership and for organisations.

The following week I’ve got a fantastic interview with Jeremy Holt, who has applied social identity to sports teams.

Holt has found that whether in Olympic teams or amateur teams, from football to volleyball, having a strong group identity is transformational for motivation. His work found that team identity was responsible for a substantial increase in team performance. His headline was that strong identities lead to teams being 53% more successful than teams with weak identities: the difference between promotion and relegation.

The genius of Jeremy’s approach is that he lays out dozens of conversations you can have with your team to gradually strengthen group identity.

Here’s the first episode with Alex.

Listen: website / Apple / Spotify

If you’re interested in understanding the compelling evidence supporting social identity theory the best training you can send yourself on is watching Alex’s brilliant presentation to the British Psychological Society:

I’d love to hear your thoughts on LinkedIn. Give it a share

Interesting exploration of how attitudes towards work are shaping the expectations of workers. ‘The Dutch are quietly shifting towards a four-day work week’

Building famous cultures is an important criteria for all great organisations. This exploration of the declining student culture of Harvard has resonance for all of us. Students turn up to lectures but have their heads down in their devices and rarely speak up. Students are chatting to each other less than ever before, sometimes even skipping lectures all together. The truth is that to change this you need to create norms (no devices, recorded attendance) that some people might consider to be illiberal. Good cultures aren’t just the easiest route, they represent our disagreement with easy

The job market is tough right now: ‘I had to do a personal statement for Greggs that was about 1000 words long’

‘I just don’t trust her’: if you’re watching The Traitors there are stronger lessons of unconscious bias in this show than in that DEI training that your firm made you do: example 1, example 2. It’s devastating to watch

Three quarters of millennial dads say they want to share the parenting load with their partners but their jobs don’t see things in the same way. One in five say when they’ve asked to take time off for family reasons they’ve been asked why their partner isn’t doing it

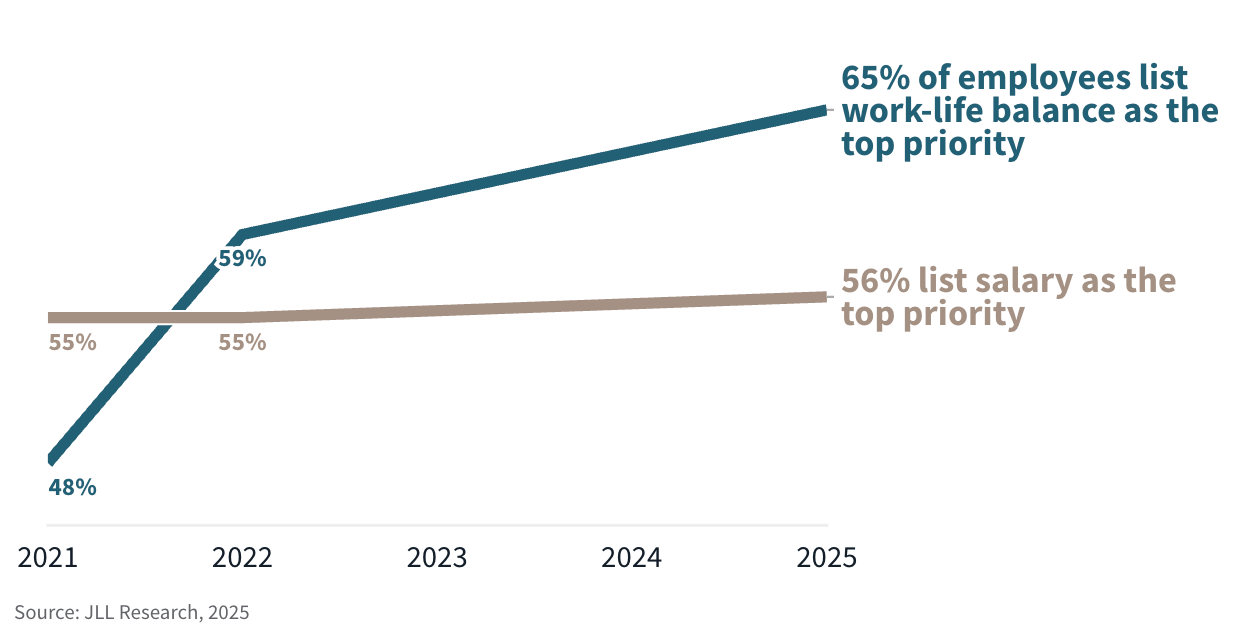

Higher pay is the top reason we seek a new job, but JLL’s 2025 Workforce Preference Barometer says flexible working is a higher priority for workers than salary if we’re staying at our company. (Also, 57% of those considering quitting blame burnout for their decision)

Someone sent me this lovely guide to making friends: ‘go where hands do things’, ‘make a specific, stupid plan’, ‘let the phone be a bridge, not a house’

When it comes to time we spend in the office, the biggest predictor is our manager’s behaviour

John Wiltshire wrote a visual account of how much office space we need to feel like we’ve got room to do our work

What others are saying about the Eat Sleep Work Repeat podcast?

“Am sitting here reading ‘The Power of Mattering’ that you recommended a while back. I bought it as I’m having a tricky time at work and actually some stuff in the early chapters made me cry. Realised this was exactly the problem… feeling like I don’t matter and have too few work friends. Anyway its made me realise a few things I can work on with my own team. Thank you.”

Listen to the episode on the Power of Mattering. If you like it, leave a review where you listen. (You’re meant to say these things to feed some horrible, toxic algorithm. I normally can’t be bothered humouring the beast)

[Re - cover letter for Gregs] Pre-pandemic, when I worked in schools, I was surprised to see that the sixth form students didn't do Saturday jobs in shops anymore; a handful of them worked in care homes. Made me think how exhausted they must be coming into school around that job.

I've nothing to add to the discussion. I just wanted to say I found this week's newsletter fascinating and thought-provoking. I love anything that empirically explores teamwork beyond the label of a group of "resources". I'm looking forward to the podcast now. Thank you, Bruce