Are we looking for the cause of Gen Z anxiety in the wrong place?

ALSO: I chat to Daniel Coyle, the author of The Culture Code

Have we reduced the independence of children so much that they struggle to cope with a transition to the world of work?

In the UK economic inactivity is strongly on the rise in those under the age of 25. Recent data from the Learning and Work Institute and the Office of National Statistics reports that almost a fifth (19.2%) of 18-to-24-year-olds are not in employment or full-time education. The ONS credits much of the rise to ‘people who were inactive because of long-term sickness’ - citing big increases in mental health challenges.

So much of contemporary discussion about young people veers into a debate about the rights or wrongs of mobile phones and social media, research is a little less certain that phones are wholly to blame.

An eye-opening post from Dani Payne, Head of Education at the Social Market Foundation might be grounds for reappraisal. In her TikTok Payne suggest that Gen Z anxiety might, at least in part, be down to the way that we withhold personal autonomy from young people.*

Dani’s original post is essential viewing:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

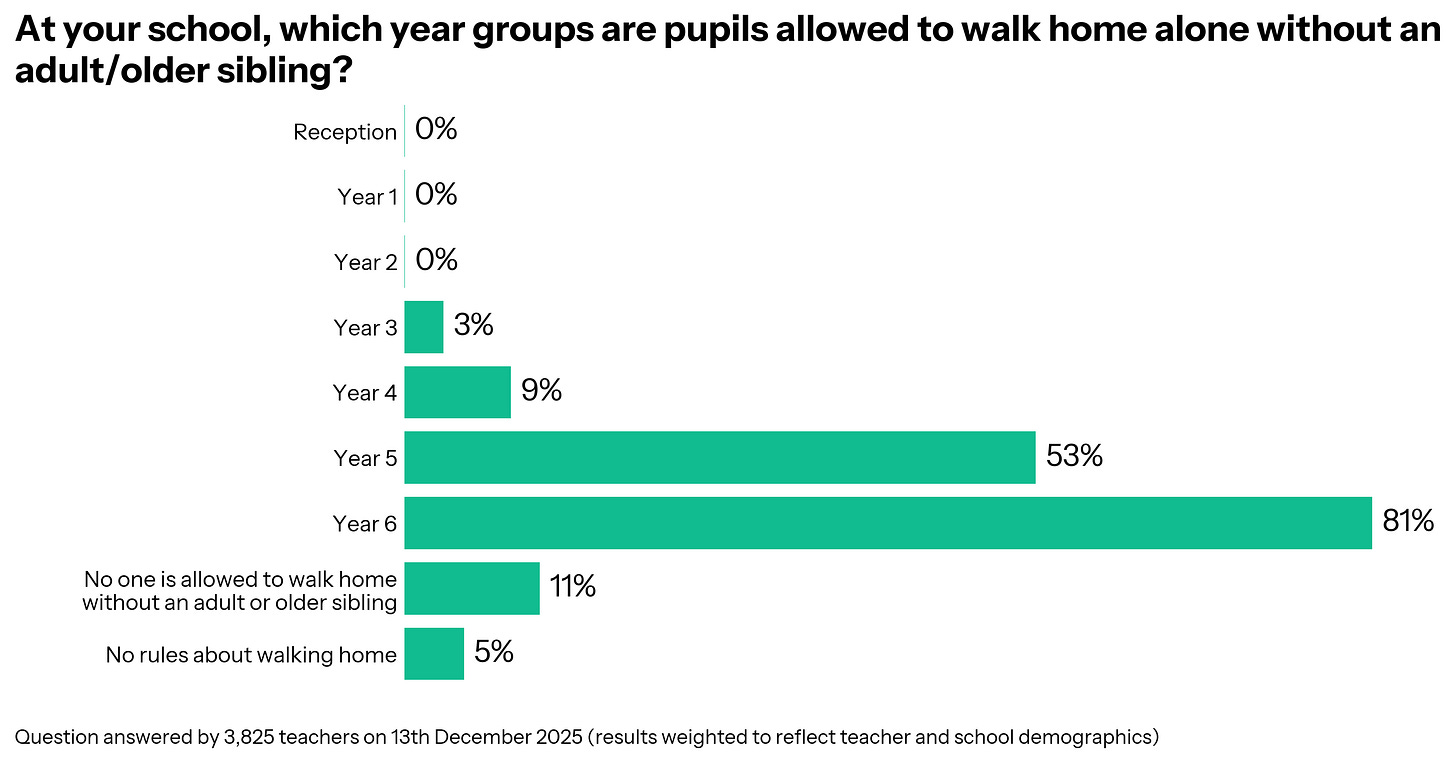

Teacher Tapp is an app used by over 10,000 teachers. It asks a daily question at the end of the school day and uses the data to report back to participants, and to inform policy makers. As Payne reports Teacher Tapp asked teachers what age children are able to talk home from their school without an adult (or older sibling):

(Reminder: Year 3: 7-8 year olds, Year 4: 8-9, Year 5: 9-10, Year 6: 10-11)

Payne says ‘Over the last few decades we’ve reduced how much independence we give to children in a major and systemic way’. Only one in 10 schools allows Year 4 pupils to walk home from school.

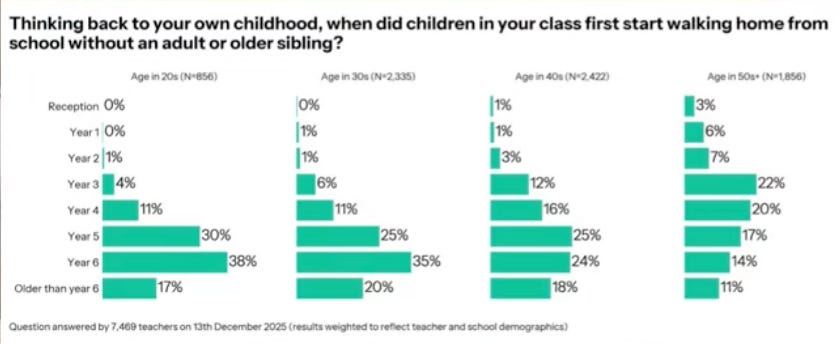

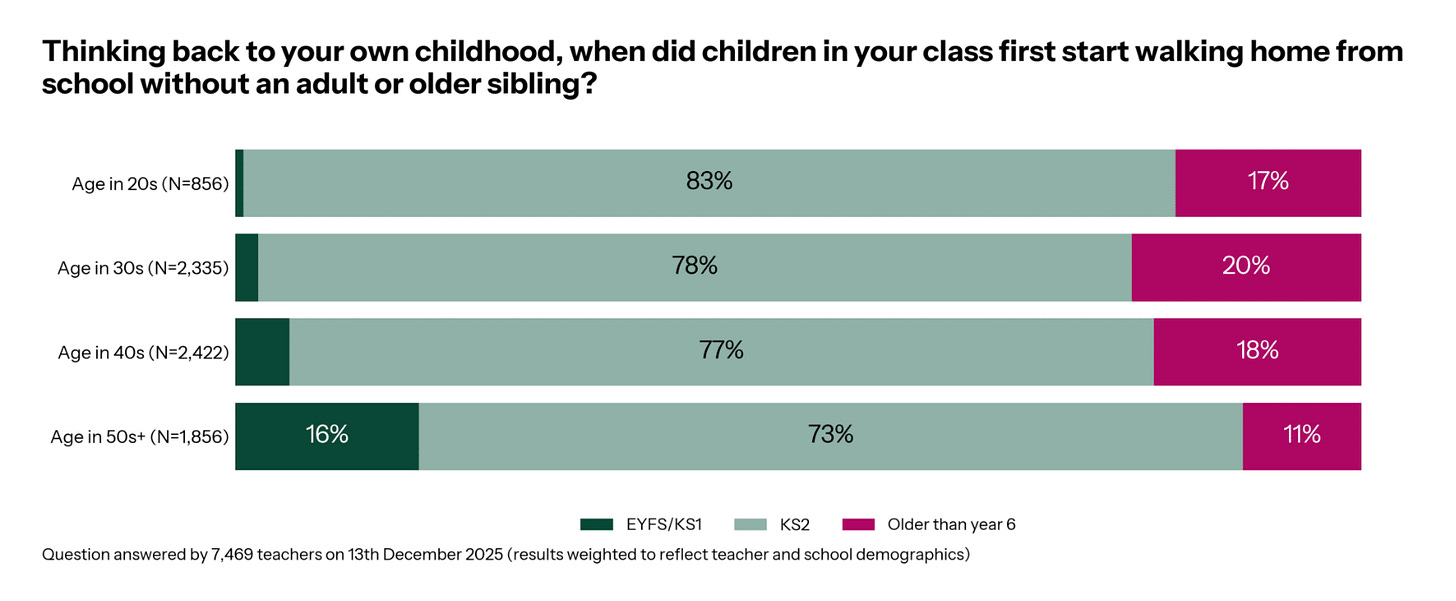

Teachers were then asked at what age they were allowed to walk home school. Looking at the data allows us to see the big shift that took place in the 1990s and beyond. Teachers in their 20s reported being allowed to walk home from Year 6, whereas teachers in their 50s reported being allowed to walk home from Year 3. The charts shows a clear upward climb in the age that independence was allowed.

Payne points out that the rise of child anxiety pre-dates the advent of mobile phones and social media, ascribing the limitations to independent play as a clear example of the impact of creating a low ‘locus of control’.

The ‘locus of control’ is a sense that our actions impact what happens to us. Independent play enables us to explore this understanding allowing us to explore risk-taking, decision making and being an individual.

Payne cites a study from the Wellcome Collection that mapped how children had seen a steady decline in how they are permitted to play: grandparents were free to roam across a whole town, the next generation could roam neighbourhoods, where today’s children are rarely allowed to play outside of their street. ‘We’ve removed independence, often in the name of safety, without grabbling with the psychological cost,’ she says.

I saw something along the same lines this week describing the transition of skateboarding from a practice of unbounded adventure, into now only found contained in adult-approved parks. (‘An activity which used to expose one at a young age to harsh realities of the world - class stratification, power dynamics, treatment of “the other”, definitions of space - and helped one define themselves in relation to these things, has become a more passive activity, woven into mainstream culture’.)

There’s two consequences for work. Firstly, clearly there’s a whole cohort of young people who might struggle to reach the workforce at all. Secondly we should recognise that a whole generation of young people have been denied the opportunity to practice independence. As Jackie Cooper recently said on the podcast, we should understand that ‘Gen Z have a visceral need for safety’. If we want to develop initiative, risk-taking and dealing with ambiguity we need to think about training these things from scratch.

There’s a truism about connection: that inconvenience is the price of community. We should recognise the benefit of friction in other areas of our lives. It might be too late to change the restrictions we placed on previous generations of children, but taking account of their needs as they arrive in the workplace might be the best next action.

*This whole post owes all credit to Dani Payne, I contacted Dani about her TikTok and as she had no plan to post it elsewhere she gave me go ahead to use the data and the argument. All credit to her, check our her TikToks, the sort of genius insight that is so much more readily found on the clock app than on LinkedIn. Says a lot about how LinkedIn is a self-promotion shop rather than a genuine space for business discussion. Thanks also to Grainne Hallahan and Laura McInerney at Teacher Tapp for the data.

Daniel Coyle, author of The Culture Code returns with reflections on forming cultures post Covid. He’s moved his attention to an examination of what contributes to us getting a fulfilling experience from work - and life.

We talk attention, community and the way that great teams demonstrate ‘group flow’. We also delve into some research by Nick Epley that I’ve covered on the newsletter, that suggests we’re terrible at predicting how interactions with other people will make us feel.

If you like this check out the previous episodes with Daniel: